"Do nothing – avagy karácsonyváró mese az elfoglalt ember kovászos kenyeréről"

Egyszer volt, hol nem volt, hetedhét országon is túl, volt egyszer egy ember. Ez az ember nagyon sokat dolgozott, nagy volt a családja, szerfölött elfoglalt volt hát, de a kenyerét mégis mindig maga sütötte, mert csak az ízlett neki és a feleségének, no meg a sok gyereküknek.

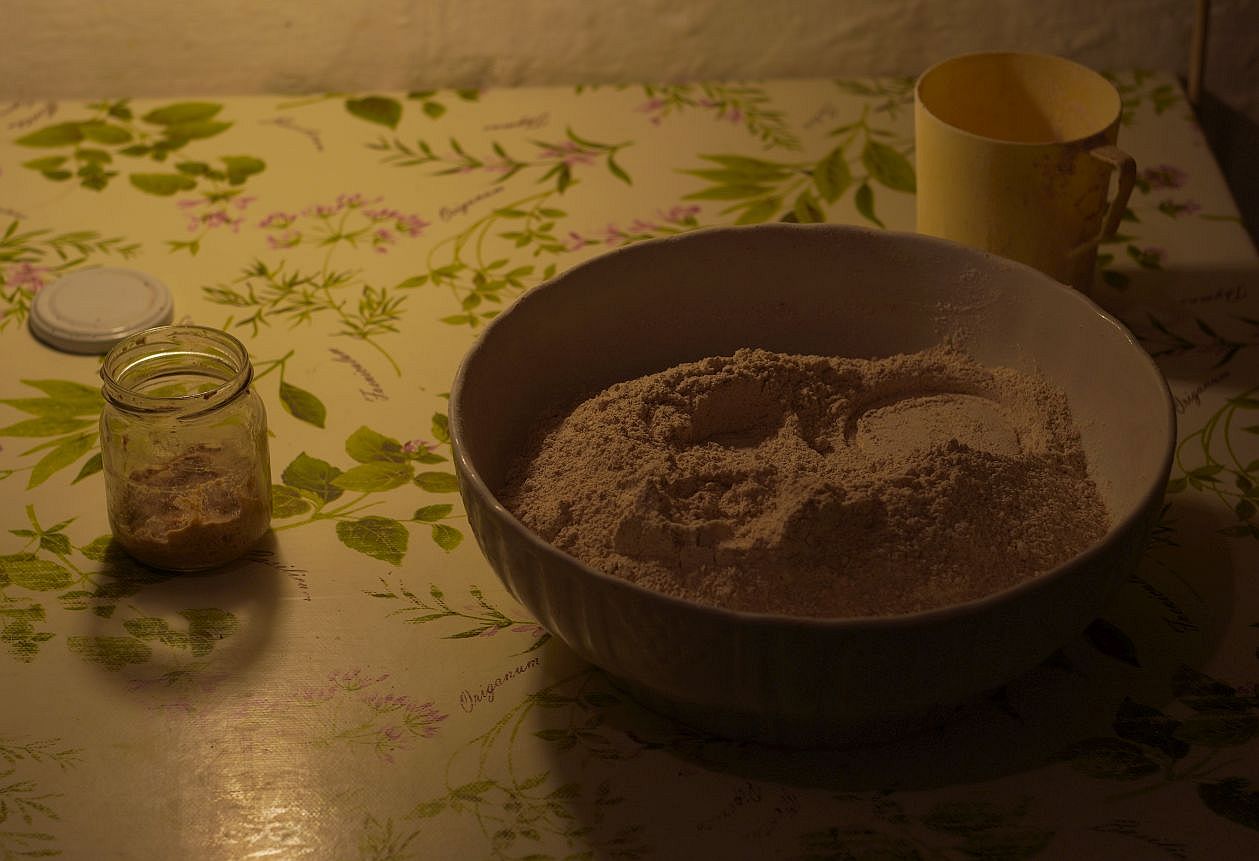

Kenyerükhöz az ember a szép, tiszta búzát jó idején, augusztusban, a kellő malmi szárítottsági fokon beszerezte, mindenféle csúszómászótól jól megőrizte.

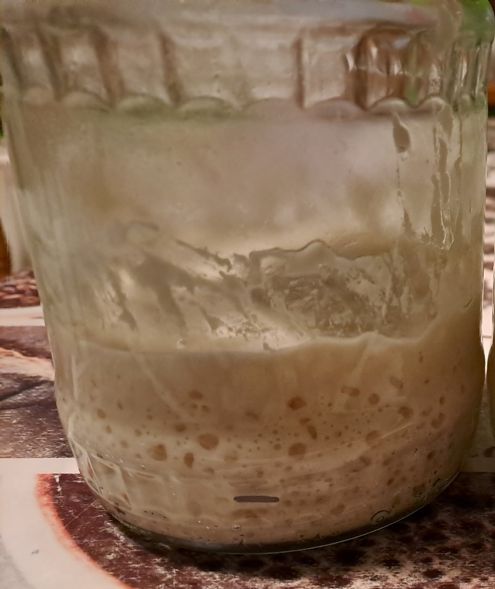

Amikor sütni akart, az ocsúból, ha olyan volt, kiválogatta, házi terménydarálóján leőrölte. A friss, illatos, teljes kiőrlésű saját búzalisztjéből a kenyerét eleinte bolti élesztővel kelesztette, de telt, múlt az idő, és az embernek egyszer csak megtetszett a nagyszülék idejéből való kovászoskenyér. Jobb is lesz az, olcsóbb is, mert élesztőért se kell a boltba menni! Nosza, azon iziben nekiállt a kovásznak, ahogyan azt a szülejétől tanulta, kereken hét nap alatt el is készült, megsüthette vele a kenyerét. Hej, ízlett a kovászoskenyér, nagyon ízlett, az embernek is, az asszonynak is, így ezután csak ilyet sütött az ember! Egy volt csak a gondja: fölöttébb nagy bajmolódással járt a kovászoskenyér, sok drága idejét elemésztette, pedig amúgy is nagyon sok volt a dolga.

De, hogy szavamat s mondásomat össze ne zavarjam, azt is tudni kell ám erről az emberről, hogy nagyon furfangos volt. Az eszét mindig azon járatta, hogy hogyan tudná a munkát minél egyszerűbben, minél kevesebb idővel és fáradozással, de úgy elvégezni, hogy abból semmi se hibázzon.

Ahogy már mondottam is, bántotta nagyon, hogy a kovászos kenyere bizony elég sok üggyel-bajjal jár, sok idejét elveszi, de mégsem akarta volna abbahagyni, hiszen a felesége azt a kenyeret, ő meg a feleségét, családját annyira szerette.

De az asszony csak pörölt vele. Azt mondja neki:

- Az már igaz, hogy nagyon jó kis pánkókat süt kend mostanában, igen falják a purdék is, de kend utóbb már folyton csak azt a kovászt abajgatja, három óránként nézögeti, kavargati, az esze mindig csak azon jár, a Jancsi gyerök mög mögbukik az oskolában! Lássa, én se írni, se olvasni nem tudok, főzök, mosok egész nap, hát kendnek köll segíteni neki a háziföladatban!

Elbúsul erre az ember, töprenkedik, bucsálódik, hogy hát akkor most mit is csináljon. Kell a jó kovászoskenyér is, de dolog is van, fát is kell vágni a tűzre, most meg még a gyerök is bukásra áll matematikából, hát hogyan legyen akkor már mostan.

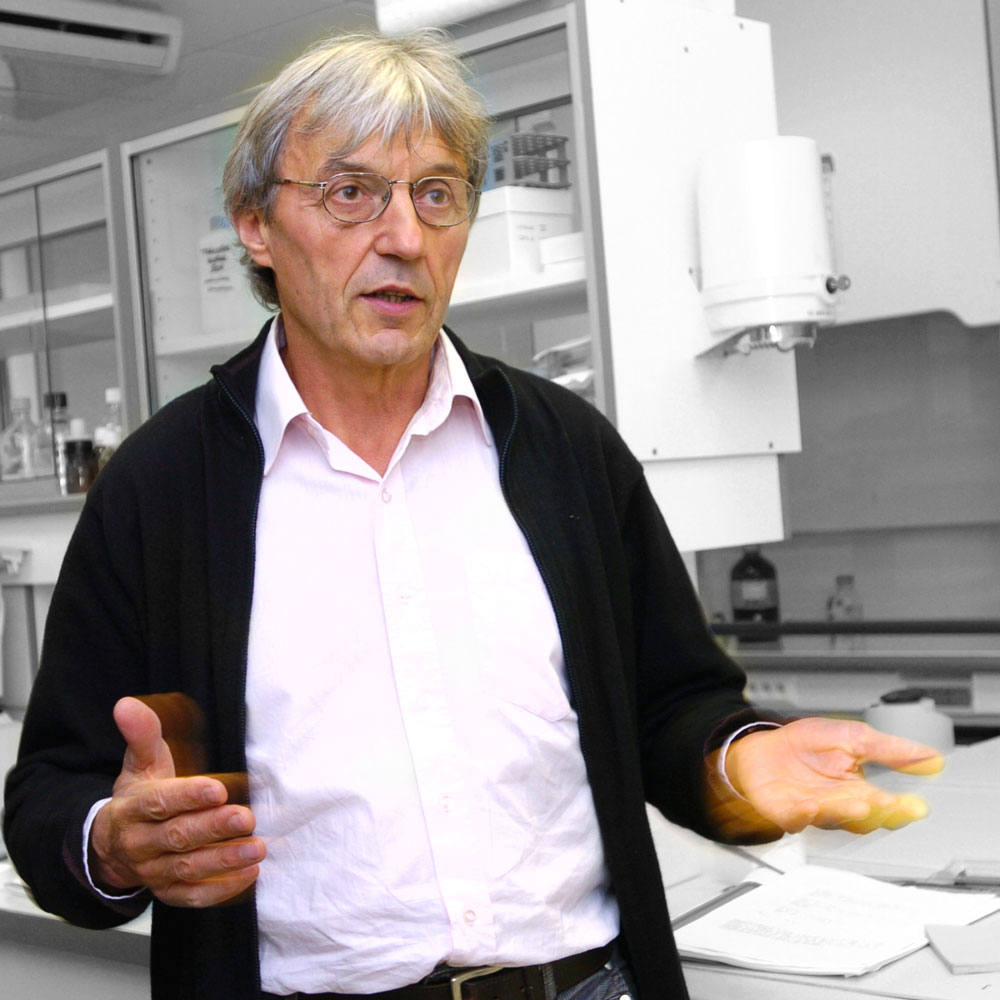

Nosza, előveszi hát a tudós könyveket, elolvas mindent, amit azok a búzáról, lisztről, kovászról, kenyérről írnak: miben is áll a búzaszem összetétele, a sikért benne milyen fehérjefajták alkotják, ezek milyen nyúlási tulajdonságokkal bírnak, miben is különbözik a durumbúza a kenyérbúzától és a többi. Addig-addig olvasott, míg egyszercsak, nagy keresésében, kutakodásában, rá nem talált az interneten Christian Rémésy, az INRA táplálkozástudományi és kutatási igazgatójának az írására. Igen megörült az ember, mert az az írás bizony reávilágított a kérdése nyitjára! A Rémésy doktor csudálatos kenyerét pedig úgy nevezik: „do nothing”, vagyis „ne tégy semmit”, mégis – azt mondják – finom lesz a kovászos kenyered a végén! Hitte is az ember, nem is, de – gondolta magában – egy életem, egy halálom, mégis megpróbálom, nem veszítek sokat, nézzük, mi sül ki belőle!

Hát láss csodát! Minden szó színigaz volt abban az írásban! Minden másképpen lett attól a naptól fogva, hogy az ember az új módit kipróbálta!

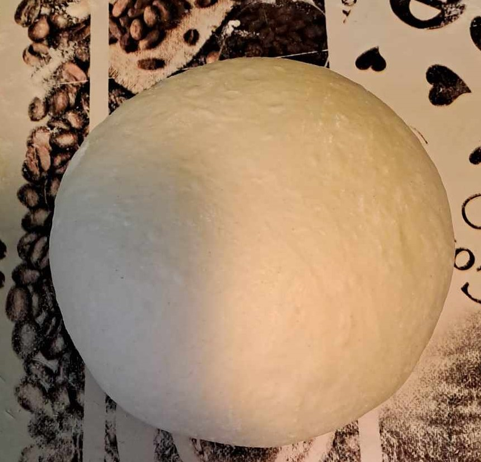

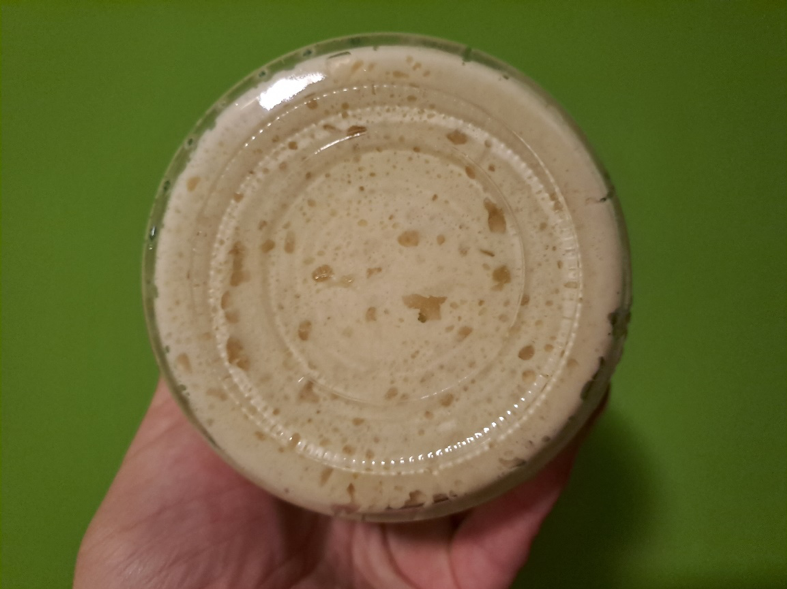

Ezután két-három naponként, dolog végeztével, este a kenyértésztáját a liszttel, egy kis kovásszal, sóval meg vízzel – mi több, fakanállal, hogy még a kezét sem kellett összeragacsoznia – percek alatt összekeverte. Egy födővel szépen letakarta, és már ugorhatott is az ágyba.

Másnap reggel, amikor fölkelt, a vizes kezével – vagy a szilikon spatulájával, ha az úri kedve éppen úgy tartotta – az addigra szépen megkelt, fényes, hólyagos kenyértésztáját a széléről befelé, körbe-körbe takarosan meghúzogatta, meghajtogatta, újra letakarta, majd egy órácska múlva már meg is süthette, és láss csodát! Már el is készült a finom, egyszerű kovászoskenyere! Keveset fáradt vele, de még jobb volt, mint a régi! El is fogyott hamar! Azóta az embert a felesége is egyre csak dicséri, mert az új kenyér minden eddiginél finomabb lett, és az embernek is sokkal több ideje lett reá meg a purdékra. Nem is bukott meg a Jancsi gyerök az oskolában, hanem még kitüntetést is kapott évvégén matematikából! Így volt, igaz volt! Aki nem hiszi, járjon utána!

Ha szeretne valaki utánajárni, most az ember (aki anonim kíván maradni) a csudás kovászoskenyere titkába, a Rémésy doktor... alábbiakban idézett szövege alapján megalkotott saját, pontos, évek óta jól bevált, nap mint nap használt receptjébe a Faluság kedves olvasóit beavatja:

Do-nothing-bread (kenyér, amelynek elkészítése során szinte semmit se kell csinálni)

100%-nak tekintve a liszt tömegét, amiből sütni akarunk,

ehhez hozzá kell adni:

a liszt tömege 1%-ának megfelelő mennyiségű kovászt*,

a liszt tömege 90%-ának megfelelő mennyiségű vizet** és

a liszt tömege 1 - 1,5%-ának megfelelő mennyiségű sót.

(Én már csak 0,5% sót használok, ez egy csapott evőkanál sót jelent 2 kg liszthez. De annak, aki bolti kenyerekhez van szokva, nem sok az 1 - 1,5% só.)

Kicsit, épphogycsak, összekeverni a tésztát, és 24 óra hosszan szobahőmérsékleten állni hagyni.

Én csak kb. 12 óra hosszan hagyom állni, de én kevesebb sót is rakok. Hőmérséklettől is függ. Célszerű a napi időbeosztáshoz igazítani. Én este keverem be, és reggel/délelőtt sütöm.

Az edényt le kell takarni. Kendő/konyharuha szerintem nem annyira jó, mert a tészta teteje kiszárad. Fedő, nem nagyon szellőző takarás jobb.

24 óra múlva sütni. Én kb. 12 óra múlva sütöm.

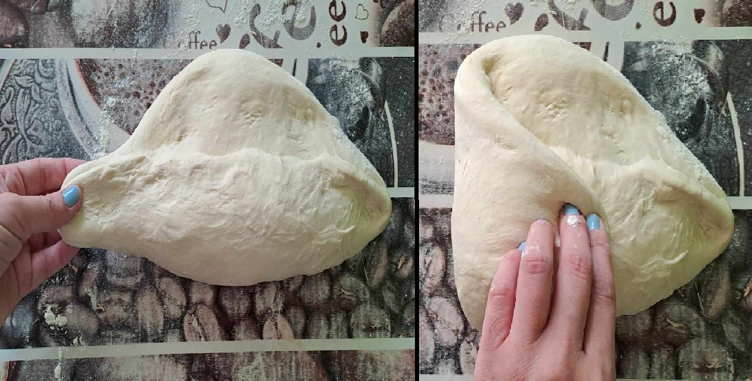

Sütés előtt 1 - 3/4 órával, ha meghajtogatjuk a tésztát (nyújtás-hajtogatás), akkor jobb lesz a kenyér állaga, szebben följön. Ennek a műveletnek az a célja, hogy a sikért gömbhéjszerűen rendezzük el. De nem kell sokra gondolni, 10-12 hajtogatás is elég. Először célszerű az edény fala mentén – egy (szilikon) spatulát körbemozgatva – elválasztani az edény falától a tésztát, utána vizes kézzel (akkor nem ragad a tészta a kézhez) – liszttel ilyenkor szerintem már nem jó vacakolni, és amúgy is az volt a cél, hogy az élesztők és a tejsavbaktériumok feldolgozzák a lisztet – kívülről befelé, az edény közepe felé meghajtogatni a tésztát.

Lehet lisztezett szakajtóba is rakni ilyenkor a tésztát, de én nem szoktam, bár korábban csináltam.

Egyszerűbb (oliva-) olajos szalvétával áttörölt és belisztezett tepsire borítani a tésztát egyben (körbemozgatni egy spatulát az edény fala mentén, hogy szakadás nélkül, egyben kerüljön a tészta a tepsire).

A sütő legyen rendesen előmelegítve.

Én a tepsin szoktam darabokra osztani, mostanában kettőre. A belisztezett tésztát késsel félbe (vagy több darabra) vágom, a vágás mentét lisztes kézzel a tészta alá göngyölöm.

A tészta tetejét csak akkor nem szoktam lisztezni, ha ilyenkor nem formázom, hanem egyben sütöm az egészet ("lapos" változat).

Éles vékony késsel be szokás vágni a tészta tetejét néhány helyen.

*kovász

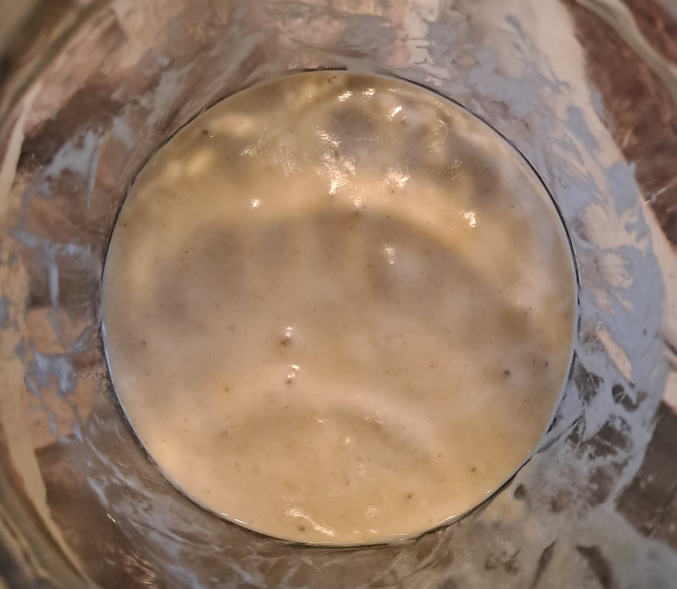

Kisebb mennyiségű, 4-5 kávéskanál mennyiségű teljeskiőrlésű lisztet kicsit langyos vízzel elkeverünk, de ne legyen túl híg, inkább sűrű, tésztaszerű.

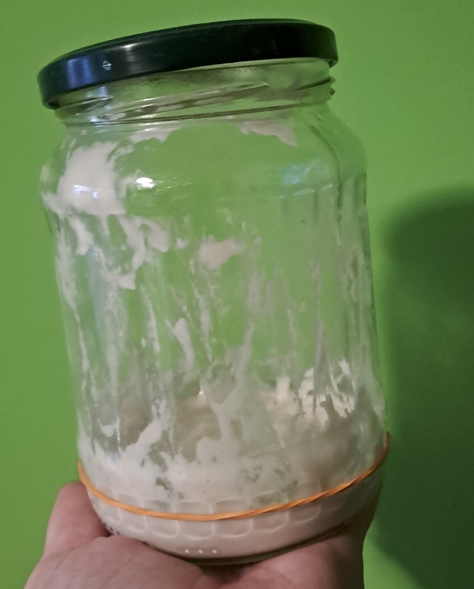

Szobahőmérsékleten tartjuk egy kis fedett edényben (pl. kis csavaros befőttesüvegben).

Naponta frissítjük. Ez abból áll, hogy egy fél kávéskanálnyit meghagyunk belőle (a többit eldobjuk, vagy valamilyen más célra fölhasználjuk), és hozzáadunk négy kávéskanál teljeskiőrlésű lisztet.

Egy hét múlva kész, lehet vele sütni.

Később jobb a kovászos edényből a kovászt minden sütéskor kiüríteni, liszttel kitörölni, és a bekevert kenyértésztából egy kávéskanálnyit beletenni, és ahhoz hozzáadni még négy kávéskanál teljeskiőrlésű lisztet. Ez 10-15 Celziusz fokon 2-3 napig még jó, nem muszáj minden nap frissíteni. De ha 2-3 nap múlva nem sütünk, akkor frissítést igényel. Szerintem 10 fok alatt nem jó tartani.

*víz

A víz mennyisége csak útmutatás. A teljeskiőrlésű lisztek több vizet vesznek föl. És ezen belül is, minden lisztnek más a vízfelvevő képessége.

Attól is függ a víz mennyisége, hogy ki milyen kenyeret szeret: lágyabbat, vagy tömörebbet.

Jól bevált szabály annyi vizet adni, amennyivel a tésztát kicsit nehezen, de még össze tudjuk keverni egy kisebb főzőkanállal.

Itt pedig elolvasható a francia Rémésy doktor – akinek köszönettel tartozunk – internetről vett korszakalkotó írása. Előrebocsátandó, hogy az alábbi szöveg feltételezhetően vagy (ismeretlen személy által) franciából van – agyamenten – angolra fordítva, vagy Rémésy doktor a történelmi hagyományok folytán hadilábon áll az angollal, de ez jó, mert fokozottan gondolkodásra készteti az olvasót.

After the excesses of the very airy white bread, the choice of the French tradition was a good strategy to improve the bread quality. A new mastery of the density of flours (type 80), salt content (16g per kilo of flour) and a longer breading fermentation to allow the action of plant enzymes is now essential to establish its nutritional quality. That is why, I clearly invite the bakery sector to move towards this new approach to breadmaking, which will require a change in breadmaking, which ultimately should be easy to implement, given its simplicity .

Originally bread was produced from kisses, with low-intensity manual kneading, natural sourdough fermentation, a very moderate addition of salt, and wood-fired cooking. Virtually all of these parameters have changed: the nature of whiter flours, more intensive kneading, faster fermentation with industrial yeast, higher salt content, more sophisticated cooking ovens. After more than a century of technological research and modernization of bakeries, bread is far from having the nutritional qualities required to make it a major food of optimal quality.

The old-fashioned bread, when good flours were available, was undoubtedly of excellent quality, however we will not find the conditions of a bygone past. However, is it not possible to develop a new approach to breadmaking, to return to the very essence of bread: a long-fermented product that needs very little salt to express its taste, a very simple product to make at room temperature, with a more moderate kneading, a very low fermenting seeding and a fermentation time of about a day or more.

It is this complete change of approach that I propose to adopt, to make bread more simply, - with type 80 flour (without any other input) to ensure the supply of fiber, minerals and micronutrients, with a extremely reduced kneading, very low yeast (or yeast) inputs (less than 1 g of yeast per kilogram of flour, or 1 to 5% of fairly liquid yeast refreshed), a very low salt content of 10 to 16 g per kilogram of flour, and a fermentation time of at least 20 hours in a chamber of 15 to 18 degrees. So a process of great simplicity, the progress of the fermentation at room temperature or slightly lower, with an elemental kneading and contributions of ferments of the most reduced. How to justify such an approach?

The choice of the type of flour.

The rise of white bread during the glorious years of post-war development has been borne by a highly artificial symbol of abundance and purity. The more the bread became white and airy, the more it lost its nutritional value and taste, and the more it became salty.

In order for the carbohydrates of bread to have the best possible metabolic effects, they must be digested slowly, but also be accompanied by a sufficient supply of minerals and micronutrients. The grain of wheat has the peculiarity of accumulating in the sound and germ three-quarters of its fibers, minerals and vitamins. The enrichment in these elements of the flour can be directly appreciated by the type of flour (defined by its ash content). This measurement is simple and there is an excellent correlation between total mineral content and that of fiber, vitamins and other micronutrients. The French bakery has made a significant progress by using mostly type 65 flour rather than 55, it must now move resolutely towards type 80. The slide towards type 80 may be gradual and no longer risk being sanctioned by regulatory constraints. Because type 80 is a good compromise to increase the nutritional density of flours without significantly changing the nature of bread, the Ministry of Health has even recommended its generalization. Type 80 is not new, since all stone mill flours were at least of this type. With the cylinder mills, an increase in the milling yield of 77 to nearly 82% by the incorporation of remouldings suffices to reach this type.

There is a more direct solution to obtain a type 80, by incorporating in flour 65, 15 to 20% whole wheat crushed or crushed and pre-quenched, or even directly without pre-soaking if the hydration and the fermentation time are high. These fractions, where the composition and structure of the grain are best preserved, fit perfectly into the crumb of bread, and are more pleasant in the mouth than crushed bran. This technique also has a major interest in valorizing organic wheat or low yielding but high nutritional quality wheat. The development of an offer of bis breads based on conventional flour and organic whole wheat is relevant because of the cleanliness of organic wheat envelopes.

Even if on average, the current bread is less white than before, it is shocking to praise the nutritional virtues of bread without giving it the means, without developing a sufficient supply of type 80 breads. Bakers should be keen to educate their customers about the nutritional value of less white breads. The process is easy and is an opportunity to start a dialogue with fans of real bread. Another major point is to stop the very high bakery value flours, which has led to the exclusion of hardy wheat varieties, which are often more resistant to disease.

Enrichment of gluten due to the selection of wheat, nitrogen fertilizers or the addition of gluten could end up affecting its good digestibility in bread. The wheat bread industry should now agree to work with more modest value bakery wheats and more balanced gluten profiles.

Reduce kneading very strongly to improve the glycemic index

White bread has been rightly criticized for having too high a glycemic index, that is to say, raising blood sugar too rapidly, which pasta does not do. In the latter, gluten continues, even after cooking, to surround and protect the starch grains (avoiding sticking). This protection helps spread the speed of digestion of starch, and avoids a rise too fast (and less durable) blood glucose.

The situation of bread is different from that of pasta. In the flour before kneading, the starch grains are surrounded by a protein network. Even if it is not very intensive, the kneading has such energy that it can reshape the gluten configuration and separate it from the starch grain. Under these conditions, there is no obstacle to the bursting of the starch grains during cooking and its too rapid digestion by the salivary and pancreatic amylases.

In fact, the more we knead, the more we seed in yeast, the more we aerate the bread through the development of a film of gluten, the more unnecessarily raises the glycemic index. The bread of the French tradition less kneaded actually has a better glycemic index than the current white bread. Sourdough breads that are more acidic and dense (such as most organic breads) also have better glycemic indexes. The products of bacterial fermentation (mainly lactic and acetic acid) also seem to contribute directly to the drop in the glycemic index of sourdough breads. The presence of sound fibers (in kisses or complete flours) generally leads to denser crumbs and the whole bread has in this case a good glycemic index, further improved by the leavening technique.

To improve the glycemic index of the bread, it is necessary to avoid that the majority of the gluten is detached from the grains of starch by softening the processes of kneading as much as possible. The ideal is to let the network grow by itself after the frasage. Then an extremely gentle kneading of 3 to 4 minutes, or very brief kneading of 1 minute to several hours apart is largely sufficient to complete the network. It should also be noted that the softening of the kneading has a very favorable impact on the staling speed of the bread. When the crystalline state of the starch is slightly altered by a very soft kneading, the processes of retrogradation will in return be much more modest and slow.

Why do we have to develop long and acidic fermentations?

The control of the fermentations of the bread is not only used to give bread a taste, it is essential to allow the expression of the enzymes of the dough. In fact there are two types of enzymes in the dough: those provided by industrial yeast or leaven consisting of lactic acid bacteria and wild yeasts, but also those provided by the flour. By using a lot of ferments, the work of the microbial enzymes is accelerated and the duration of the fermentation is reduced, which has the disadvantage of not allowing the specific enzymes of the flour time to act, especially since We proceeded to the cold. In fact, the main role of microbial ferments is to create favorable conditions for the action of plant enzymes. In fact, these enzymatic activities are fully expressed only if the pH of the dough reaches values close to 5. The production of organic acids (lactic, acetic) by lactic acid bacteria heterofermentaires is therefore essential for the enzymatic work of breadmaking.

These activities include the action of phytase, which destroys phytic acid and increases the bioavailability of minerals, and proteases that split gluten into shorter fragments, liquefying it if allowed to. this enzymatic work is prolonged too long. All the paradoxical art of baking is to raise the bread through the gluten network but also to begin its degradation to promote digestion. The adoption of these very long pointing at high temperature can of course be secured at the end of the journey by storage at 4-6 degrees, when optimal enzymatic work is ensured.

The major characteristic of a natural breadmaking is therefore its ability to lower the pH to allow the expression of the enzymes of the dough. According to this purpose, a short fermentation with yeast is difficult to accept, since it does not allow a sufficient lowering of the pH and the expression of enzymatic activities essential to the nutritional quality of the bread. To obtain a pH close to 5 in the dough with yeast seeding, it takes a long enough fermentation time (15 to 18 hours) at room temperature or a little lower (15 degrees). These conditions make it possible to considerably reduce yeast seeding. Acidification of pH can be induced by the development of ambient lactic acid bacteria, but it is much safer to add a minimum of starter.

A new control of the fermentations and the monitoring of the pH of the dough should therefore be developed to fight in particular against gluten intolerances. When the risk of intolerance to gluten was very low, the acidification of the dough might seem superfluous for a white flour low in phytic acid, it is now essential for the partial hydrolysis of gluten. This new mastery of acidification should also help bakers improve breadmaking.

Yeast has seemed to be very useful, but it is far from replicating the complexity of the fermentative activities of a natural yeast, rich in lactic-acetic bacteria and wild yeasts. The use of yeast for rapid emergence has led to a complete neglect of the action of flour enzymes. With or without natural leaven, panary fermentation should allow the sufficient development of a lactic flora and fermentation with short yeast at room temperature or long cold is not ideal nutritionally. Moreover, the term "bread of French tradition", by its reference to the past of the bread, should be able to be a guarantee of a conduct of the fermenting acid sufficiently acidic, which is totally absent from the current specifications. Finally, in the current situation, the two main flavors of bread are too often those of yeast and salt, which is far from the basic taste of bread, in which a very moderate acidity plays a fundamental role as in many other dishes. other foods.

Reduce the salt content of the bread very much.

To prevent high blood pressure causing many vascular disorders and in particular Stroke, we should ingest as little salt as possible, at least not to exceed the daily dose of 5 gr per day (it is more than 8 gr on average in the French population). We know how much the bakery sector finds this ingredient useful under the pretext of technological effect, control of fermentations, while its main role is to give bread a taste when it is too much kneaded. The Ministry's National Health and Nutrition Program has been able to recommend an acceptable level of 18 grams per kilogram of flour, but this very timid recommendation has not even been widely followed. It can only be observed that the proportion of very salty breads has significantly decreased. However, with contents often close to 20 gr per kilo of flour, the situation is not credible in terms of prevention of hypertension, especially since bread is often consumed with salty foods such as cold cuts and cheeses.

A serious proposal in terms of public health would be to generalize a content of 16 gr of salt per kilo of flour by regulation, so that the bread is no longer the major food source of salt. A content of 16 gr is largely acceptable in terms of taste, and can even hide the true taste of bread. Even at this dose, the salt is penalizing for the fermentations, but the ideal is to be able to reduce the quantities of yeast and to develop these acid fermentations so useful to partially degrade the gluten.

After the excesses of the very airy white bread, the choice of the French tradition was a good strategy to improve the bread quality. A new mastery of the density of flours (type 80), salt content (16g per kilo of flour) and a longer breading fermentation to allow the action of plant enzymes is now essential to establish its nutritional quality. That is why, I clearly invite the bakery sector to move towards this new approach to breadmaking, which will require a change in breadmaking, which ultimately should be easy to implement, given its simplicity .

Christian Rémésy

Nutritionist and Research Director INRA

Christian Rémésy

Az eredeti francia szöveg lelőhelye: https://www.latribunedesmetiers.fr/remesy-22/